Episodic ataxia (EA) is a neurological condition that impairs movement. It’s rare, affecting less than 0.001 percent of the population. People who have EA experience episodes of poor coordination and/or balance (ataxia) which can last from several seconds to several hours.

There are at least eight recognized types of EA. All are hereditary, though different types are associated with different genetic causes, ages of onset, and symptoms. Types 1 and 2 are the most common.

Read on to find more about EA types, symptoms, and treatment.

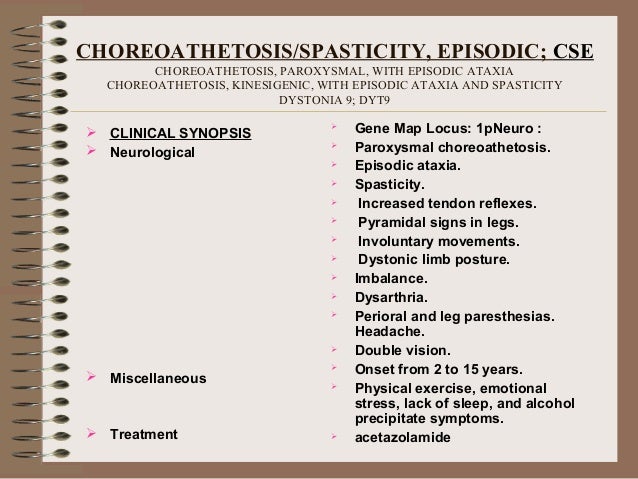

Cerebellar ataxia and cerebellar degeneration are common to all types, but other signs and symptoms, as well as age of onset, differ depending on the specific gene mutation. Episodic ataxia (EA). There are seven recognized types of ataxia that are episodic rather than progressive — EA1 through EA7. EA1 and EA2 are the most common.

Symptoms of episodic ataxia type 1 (EA1) typically appear in early childhood. A child with EA1 will have brief bouts of ataxia that last between a few seconds and a few minutes. These episodes can occur up to 30 times per day. They may be triggered by environmental factors such as:

- fatigue

- emotional or physical stress

With EA1, myokymia (muscle twitch) tends to occur between or during ataxia episodes. People who have EA1 have also reported difficulty speaking, involuntary movements, and tremors or muscle weakness during episodes.

People with EA1 can also experience attacks of muscle stiffening and muscle cramps of the head, arms, or legs. Some people who have EA1 also have epilepsy.

EA1 is caused by a mutation in the KCNA1 gene, which carries the instructions to make a number of proteins required for a potassium channel in the brain. Potassium channels help nerve cells generate and send electrical signals. When a genetic mutation occurs, these signals may be disrupted, leading to ataxia and other symptoms.

This mutation is passed on from parent to child. It’s autosomal dominant, which means that if one parent has a KCNA1 mutation, each child has a 50 percent chance of getting it, too.

Episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2) usually appears in childhood or early adulthood. It’s characterized by episodes of ataxia that last hours. However, these episodes occur less frequently than with EA1, ranging from one or two per year to three to four per week. As with other types of EA, episodes can be triggered by external factors such as:

- stress

- caffeine

- alcohol

- medication

- fever

- physical exertion

People who have EA2 may experience additional episodic symptoms, such as:

- difficulty speaking

- ringing in the ears

Other reported symptoms include muscle tremors and temporary paralysis. Repetitive eye movements (nystagmus) may occur between episodes. Among people with EA2, approximately

Similar to EA1, EA2 is caused by an autosomal dominant genetic mutation that’s passed on from parent to child. In this case, the affected gene is CACNA1A, which controls a calcium channel.

This same mutation is associated with other conditions, including familiar hemiplegic migraine type 1 (FHM1), progressive ataxia, and spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6).

Other types of EA are extremely rare. As far as we know, only types 1 and 2 have been identified in more than one family line. As a result, little is known about the others. The following information is based on reports within single families.

- Episodic ataxia type 3 (EA3). EA3 is associated with vertigo, tinnitus, and migraine headaches. Episodes tend to last a few minutes.

- Episodic ataxia type 4 (EA4). This type was identified in two family members from North Carolina, and is associated with late-onset vertigo. EA4 attacks typically last several hours.

- Episodic ataxia type 5 (EA5). Symptoms of EA5 appear similar to those of EA2. However, it’s not caused by the same genetic mutation.

- Episodic ataxia type 6 (EA6). EA6 has been diagnosed in a single child who also experienced seizures and temporary paralysis on one side.

- Episodic ataxia type 7 (EA7). EA7 has been reported in seven members of a single family over four generations. As with EA2, onset was during childhood or young adulthood and attacks last hours.

- Episodic ataxia type 8 (EA8). EA8 has been identified among 13 members of an Irish family over three generations. Ataxia first appeared when the individuals were learning to walk. Other symptoms included unsteadiness while walking, slurred speech, and weakness.

Symptoms of EA occur in episodes that can last several seconds, minutes, or hours. They may occur as little as once per year, or as often as several times per day.

In all types of EA, episodes are characterized by impaired balance and coordination (ataxia). Otherwise, EA is associated with a wide range of symptoms which appear to vary a lot from one family to the next. Symptoms can also vary between members of the same family.

Other possible symptoms include:

- blurred or double vision

- dizziness

- involuntary movements

- muscle twitching (myokymia)

- muscle spasms (myotonia)

- muscle cramps

- muscle weakness

- nausea and vomiting

- repetitive eye movements (nystagmus)

- ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- slurred speech (dysarthria)

- temporary paralysis on one side (hemiplegia)

- tremors

- vertigo

Sometimes, EA episodes are triggered by external factors. Some known EA triggers include:

- alcohol

- caffeine

- diet

- fatigue

- hormonal changes

- illness, especially with fever

- medication

- physical activity

- stress

More research needs to be done to understand how these triggers activate EA.

Episodic ataxia is diagnosed using tests such as a neurological examination, electromyography (EMG), and genetic testing.

After diagnosis, EA is typically treated with anticonvulsant/antiseizure medication. Acetazolamide is one of the most common drugs in the treatment of EA1 and EA2, though it’s more effective in treating EA2.

Alternative medications used to treat EA1 include carbamazepine and valproic acid. In EA2, other drugs include flunarizine and dalfampridine (4-aminopyridine).

Your doctor or neurologist might prescribe additional drugs to treat other symptoms associated with EA. For instance, amifampridine (3,4-diaminopyridine) has proved useful in treating nystagmus.

In some cases, physical therapy may be used alongside medication to improve strength and mobility. People who have ataxia might also consider diet and lifestyle changes to avoid triggers and maintain overall health.

Additional clinical trials are required to improve treatment options for people with EA.

There’s no cure for any type of episodic ataxia. Though EA is a chronic condition, it doesn’t affect life expectancy. With time, symptoms sometimes go away on their own. When symptoms persist, treatment can often help ease or even eliminate them altogether.

Talk to your doctor about your symptoms. They can prescribe helpful treatments that help you maintain a good quality of life.

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 | |

|---|---|

| Other names | DiseasesDB = 12339 |

| This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6) is a rare, late-onset, autosomal dominant disorder, which, like other types of SCA, is characterized by dysarthria, oculomotor disorders, peripheral neuropathy, and ataxia of the gait, stance, and limbs due to cerebellar dysfunction. Unlike other types, SCA 6 is not fatal. This cerebellar function is permanent and progressive, differentiating it from episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2) where said dysfunction is episodic. In some SCA6 families, some members show these classic signs of SCA6 while others show signs more similar to EA2, suggesting that there is some phenotypic overlap between the two disorders. SCA6 is caused by mutations in CACNA1A, a gene encoding a calcium channel α subunit. These mutations tend to be trinucleotide repeats of CAG, leading to the production of mutant proteins containing stretches of 20 or more consecutive glutamine residues; these proteins have an increased tendency to form intracellular agglomerations. Unlike many other polyglutamine expansion disorders expansion length is not a determining factor for the age that symptoms present.

Signs and symptoms[edit]

SCA6 is typified by progressive and permanent cerebellar dysfunction. These cerebellar signs include ataxia and dysarthria, likely caused by cerebellar atrophy. Prior to diagnosis and the onset of major symptoms, patients often report a feeling of 'wooziness' and momentary imbalance when turning corners or making rapid movements. The age at which symptoms first occur varies widely, from age 19 to 71, but is typically between 43 and 52. Other major signs of SCA6 are the loss of vibratory and proprioceptive sensation and nystagmus.[1]

While most patients present with these severe progressive symptoms, others, sometimes within the same family, display episodic non-progressive symptoms more similar to episodic ataxia. Still others present with symptoms common to both SCA6 and familial hemiplegic migraine.

Pathophysiology[edit]

Most cases of SCA6 are a result of CAG repeat expansion beyond the normal range, i.e., more than 19 repeats, in the Cav2.1 calcium channel encoding gene CACNA1A.[1] This gene has two splice forms, 'Q-type' and 'P-type', and the polyglutamine coding CAG expansion occurs in the P-type splice form. This form is expressed heavily in the cerebellum where it is localized in Purkinje cells. In Purkinje cells from SCA6 patients, mutant Cav2.1 proteins form ovular intracellular inclusions, or aggregations, similar in many ways to those seen in other polyglutamine expansion disorders such as Huntington's disease. In cell culture models of the disease, this leads to early apoptotic cell death.[2]

Mutant channels that are able to traffic properly to the membrane have a negatively shifted voltage-dependence of inactivation. The result of this is that the channels are active for a shorter amount of time and, consequently, cell excitability is decreased.[3]

There are also a number of point mutations resulting in patients with phenotypes reminiscent of episodic ataxia and SCA6 (C271Y, G293R and R1664Q) or familial hemiplegic migraine and SCA6 (R583Q and I1710T). C287Y and G293R are both located in the pore region of domain 1 and are present in a single family each. Expression of these mutant channels results in cells with drastically decreased current density compared to wild-type expressing cells. In cell-based assays, it was found that these mutant channels aggregate in the endoplasmic reticulum, not dissimilar from that seen in the CAG expansion mutants above.[4] R1664Q is in the 4th transmembrane spanning segment of domain 4 and, presumably, affects the channel's voltage dependence of activation.[5] Little is known about the point mutations resulting in overlapping phenotypes of familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia. R583Q is present in the 4th transmembrane spanning region of domain 2 while the I1710T mutation is segment 5 of domain 4.[6][7]

Diagnosis[edit]

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Diagnosis is done via genetic testing. Your Neurologist can administer the test. Spinocerebellar Ataxia is often misdiagnosed as other diseases such as ALC or Parkinson's Disease.

Screening[edit]

There is no known prevention of spinocerebellar ataxia. Those who are believed to be at risk can have genetic sequencing of known SCA loci performed to confirm inheritance of the disorder.

Treatment[edit]

There are no drug based treatments currently available for SCA Type 6. Physical Therapy, Speech Pathology can help patients manage the symptoms.

Prognosis[edit]

Episodic Ataxia Type 2 Prognosis

There is currently no cure for SCA 6; however, there are supportive treatments that may be useful in managing symptoms.

Epidemiology[edit]

The prevalence of SCA6 varies by culture. In Germany, SCA6 accounts for 10-25% of all autosomal dominant cases of SCA (SCA itself having a prevalence of 1 in 100,000).[8][9] This prevalence in lower in Japan, however, where SCA6 accounts for only ~6% of spinocerebellar ataxias.[10] In Australia, SCA6 accounts for 30% of spinocerebellar ataxia cases while 11% in the Dutch.[11][12]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abZhuchenko O, Bailey J, Bonnen P, Ashizawa T, Stockton D, Amos C, Dobyns W, Subramony S, Zoghbi H, Lee C (1997). 'Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA6) associated with small polyglutamine expansions in the alpha 1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel'. Nat Genet. 15 (1): 62–9. doi:10.1038/ng0197-62. PMID8988170.

- ^Ishikawa K, Fujigasaki H, Saegusa H, Ohwada K, Fujita T, Iwamoto H, Komatsuzaki Y, Toru S, Toriyama H, Watanabe M, Ohkoshi N, Shoji S, Kanazawa I, Tanabe T, Mizusawa H (1999). 'Abundant expression and cytoplasmic aggregations of [alpha]1A voltage-dependent calcium channel protein associated with neurodegeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 6'. Hum Mol Genet. 8 (7): 1185–93. doi:10.1093/hmg/8.7.1185. PMID10369863.

- ^Toru S, Murakoshi T, Ishikawa K, Saegusa H, Fujigasaki H, Uchihara T, Nagayama S, Osanai M, Mizusawa H, Tanabe T (2000). 'Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 mutation alters P-type calcium channel function'. J Biol Chem. 275 (15): 10893–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.15.10893. PMID10753886.

- ^Wan J, Khanna R, Sandusky M, Papazian D, Jen J, Baloh R (2005). 'CACNA1A mutations causing episodic and progressive ataxia alter channel trafficking and kinetics'. Neurology. 64 (12): 2090–7. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000167409.59089.C0. PMID15985579.

- ^Tonelli A, D'Angelo M, Salati R, Villa L, Germinasi C, Frattini T, Meola G, Turconi A, Bresolin N, Bassi M (2006). 'Early onset, non fluctuating spinocerebellar ataxia and a novel missense mutation in CACNA1A gene'. J Neurol Sci. 241 (1–2): 13–7. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2005.10.007. PMID16325861.

- ^Alonso I, Barros J, Tuna A, Coelho J, Sequeiros J, Silveira I, Coutinho P (2003). 'Phenotypes of spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 and familial hemiplegic migraine caused by a unique CACNA1A missense mutation in patients from a large family'. Arch Neurol. 60 (4): 610–4. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.4.610. hdl:10400.16/349. PMID12707077.

- ^Kors E, Vanmolkot K, Haan J, Kheradmand Kia S, Stroink H, Laan L, Gill D, Pascual J, van den Maagdenberg A, Frants R, Ferrari M (2004). 'Alternating hemiplegia of childhood: no mutations in the second familial hemiplegic migraine gene ATP1A2'. Neuropediatrics. 35 (5): 293–6. doi:10.1055/s-2004-821082. PMID15534763.

- ^Riess O, Schöls L, Bottger H, Nolte D, Vieira-Saecker A, Schimming C, Kreuz F, Macek M, Krebsová A, Klockgether T, Zühlke C, Laccone F (1997). 'SCA6 is caused by moderate CAG expansion in the alpha1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel gene'. Hum Mol Genet. 6 (8): 1289–93. doi:10.1093/hmg/6.8.1289. PMID9259275.

- ^Schöls L, Amoiridis G, Büttner T, Przuntek H, Epplen J, Riess O (1997). 'Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: phenotypic differences in genetically defined subtypes?'. Ann Neurol. 42 (6): 924–32. doi:10.1002/ana.410420615. PMID9403486.

- ^Watanabe H, Tanaka F, Matsumoto M, Doyu M, Ando T, Mitsuma T, Sobue G (1998). 'Frequency analysis of autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias in Japanese patients and clinical characterization of spinocerebellar ataxia type 6'. Clin Genet. 53 (1): 13–9. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0004.1998.531530104.x. PMID9550356.

- ^Storey E, du Sart D, Shaw J, Lorentzos P, Kelly L, McKinley Gardner R, Forrest S, Biros I, Nicholson G (2000). 'Frequency of spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7 in Australian patients with spinocerebellar ataxia'. Am J Med Genet. 95 (4): 351–7. doi:10.1002/1096-8628(20001211)95:4<351::AID-AJMG10>3.0.CO;2-R. PMID11186889.

- ^Sinke R, Ippel E, Diepstraten C, Beemer F, Wokke J, van Hilten B, Knoers N, van Amstel H, Kremer H (2001). 'Clinical and molecular correlations in spinocerebellar ataxia type 6: a study of 24 Dutch families'. Arch Neurol. 58 (11): 1839–44. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.11.1839. PMID11708993.

External links[edit]

Episodic Ataxia Symptoms

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

- sca6 at NIH/UW GeneTests